Organic Design for Command and Control - for Agents

John Boyd, Ralph Wiggum, OODA Loops, and Leadership

Like many software devs, I was inspired by the recent hype around Agents to rethink how I approach software engineering with agents. A couple of articles that particularly resonated with me were Geoffrey Huntley's "Everything is a Ralph Loop" (https://ghuntley.com/loop/) and Steve Yegge's "Welcome to GasTown" (https://steve-yegge.medium.com/welcome-to-gas-town-4f25ee16dd04). Both serve as excellent gateways to agentic coding by shaking up and challenging traditional thinking. If you get nothing else out of this article, at the very least go follow them and read what they have to say if you're in software engineering.

Anyway, once you start thinking in loops, like Huntley says in his article, you really start to notice them everywhere! A few years ago, I went down a similar rabbit hole after stumbling across a podcast about Col. John Boyd and what he called “OODA Loops.”

A little about Col. John Boyd: Boyd was one of the most influential military strategists of the late 20th century (and served as one of the inspirations for Maverick in Top Gun). His work is largely considered a modern counterpart to Sun Tzu’s Art of War and still inspires military strategy around the world. The military stuff isn’t important here. What matters is that Boyd talked a lot about loops.

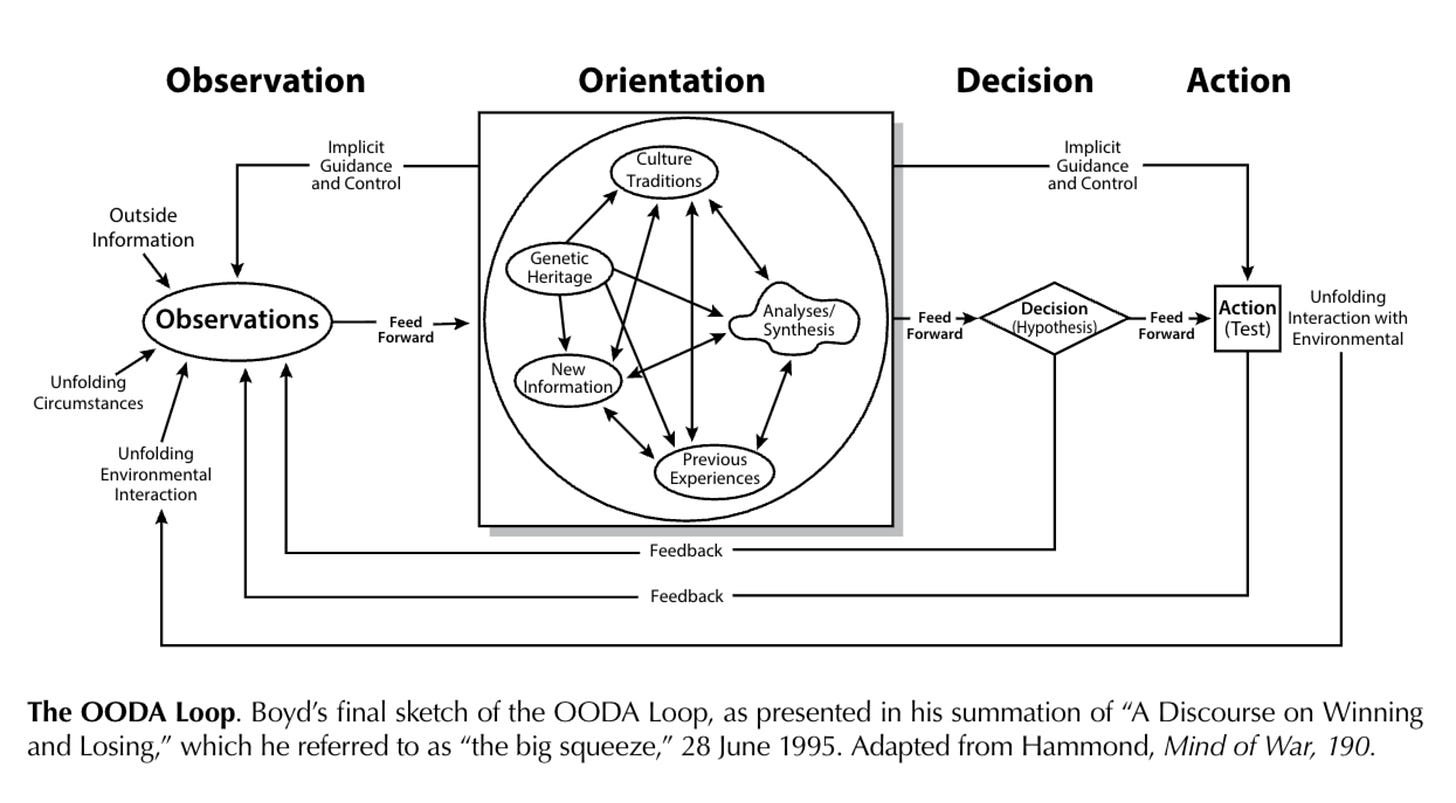

The OODA Loop

OODA Loop stands for: Observation-Orientation-Decision-Action. Boyd argued that when doing anything, everyone cycles through these stages. We make an observation, orient ourselves based on it, decide what to do, take action, and then start over in an endless loop. Success in conflict usually comes down to having a faster OODA loop than your opponent. Plenty of influencer types have written extensively about how this concept applies to all sorts of things from sports to business to relationships etc, but it’s not a difficult leap to see how it applies to AI agents.

Observation: The agent’s context window, what the agent knows

Orientation: What direction is the agent pointed? What’s the overall goal? What are we trying to accomplish? What did we do previously? What should we do next?

Decision: What should we do to achieve our next goal? What tools do we have? Which should we use?

Action: Call a tool / Do a thing / Write a response (send an email, run a bash command, buy a crypto coin, post to moltbook, etc.)

Rinse and repeat.

This framing is useful because most problems with agentic loops trace back to a failure in one of these specific types of steps.

Examples: Coding agents often fail at the Observation step. After taking an action, the agent lacks access to the output it needs to correctly observe the effect of what it just did. It’s missing access to logs, databases, or browsers, or compaction causes important details to get dropped from context. If it can’t see these things then the agent loses the ability to orient itself in the environment and the loop fails.

A failure at the Orientation step might look like the agent going off on a tangent, wasting tokens on things irrelevant to your project or compaction causing it to lose track of its tasks. The agent loses alignment and goes on to make bad decisions because of that.

A failure at the Decision step may look like: choosing a suboptimal approaches, or doing things in the wrong order that cause the loop to break. A failure in Action might be calling the wrong tool or hallucinating a tool that doesn’t exist. etc etc

Regardless of which step causes the failure, you often know a failure has occurred when the agent falls back to requiring human intervention or gets stuck. It can’t observe properly so it asks the human to check a log or test a feature or the agent gets lost hill-climbing looking for the information it needs only to get lost. Or maybe a tool is missing so it asks the human to run the steps manually. etc etc.

Once you see agentic loops this way, it become obvious that the primary path to improving an agent’s speed within an OODA loop is removing the one bottle neck that slows everything down the most. That bottle neck is the human in the loop. The bottle neck is you. Geoffrey Huntley says in many of his videos that the goal is to “sit on top of the loop,” not “in the loop.” Getting the human out of the loop means doing the engineering work to improve the agent’s ability to cycle through observation-orientation-decision-action without human intervention.

But hang with me. That’s not the main thing I wanted to talk about.

Principles of Organic Command and Control for Agents

Once you realize that dependency on humans is the bottleneck slowing down agentic OODA loops the most, you gradually conclude that you need a better way to control these agents without getting in their way. I confess that when I first looked at Yegge’s article on Gas Town, it seemed crazy and needlessly complex. The natural question was “why would you even need this?” But I think Boyd can help us understand why orchestrators and autonomous loops are built the way they are. Its a remaking of the command and control structures we use for a different era of software development. We need to think differently.

In addition to the OODA Loop, Boyd gave a briefing on Organic Designs for Command and Control (https://www.coljohnboyd.com/#pdf-organic-design-command-control-pdf) Boyd’s whole presentation is relevant to the discussion, but I’ll highlight one part for now:

Boyd theorized that effective command and control means giving units agency to take actions. He didn’t even like the term “Command and Control.” “Command” implies rigidity and restriction. “Control” to him implied friction. According to Boyd, friction and restriction slow down OODA loops, inhibit creativity and flexibility, and lead to failures and an inability to respond fluidly to the chaos of real world situations.

Instead of command and control, Boyd suggested thinking in terms of “leadership” and “appreciation.” To Boyd, true leadership wasn’t about issuing commands that had to be rigidly followed. It was about inspiring shared intention and alignment. Instead of getting bogged down making every decision (micromanaging slows the OODA loop), leadership is about making sure every actor has “orientation” toward the same goal. “Appreciation”, he argued, is what makes this style of leadership possible.

This isn’t a warm, fuzzy “thank you, Claude.” It’s about having observability into what your army of agents is marching toward, having your finger on the pulse, so you can appreciate what’s really happening. Instead of dictating from an ivory tower with no windows, true leaders use this appreciation to gauge alignment and orientation and course-correct if actors start to drift. Boyd described this sort of alignment as “implicit guidance and control” through shared orientation. Shared alignment allowed great military commanders throughout history to lead their armies to victory by granting their subordinates agency to adapt on the battle field without being tied to rigid, and slow, command structures.

The key insight is this: we can fall into the trap of trying to control our AI Agents too tightly. This messes up our agents’ OODA loops by hamstringing their flexibility and forcing them to be dependent on humans. Not only is this slow, It ironically robs agents of… agency.

If we apply Boyd’s theory, the goal should be to align agents on high-level goals, guidelines, and principles while giving them flexibility within their own OODA loops to act decisively and creatively. Create implicit guidance and control through proper orientation, treating each agent as a cell of intelligence with agency to act based on shared orientation. With this philosophy, it is often better to be less prescriptive with tasks because we want to give agents head room to do their work. Room to be smart and adapt as needed. (As a quick aside, this also means that we should be very selective about what we let into our agents context window and system prompts because these impact orientation. Boyd talks about an idea here called “non-cooperative centers of gravity”. I’ll maybe talk about that in a different post - but Practically I think frivolous soul.md files, tons of skills, and most “memories” are usually detrimental to agent performance because they contain competing orientations and distract from aligned orientation to the specific tasks at hand. Additionally it also underscores some of the reason why we should leave our models context window to play with instead of filling it up with a bunch of “helpful” commands and requirements. It turns out agentic coding is fundamentally an alignment problem.)

Regardless, If granting agents this much freedom makes you uncomfortable, we should work towards a solution instead of abandoning autonomous agentic coding as a concept. Add observability. Work with your agents to define better specs. Work with your agents to write better guidelines that work well with the quirks of your individual models, loops, and agents. Create better monitoring so you can appreciate what your agents are actually doing. Tune everything until you have a shared alignment that stays on track through loop iterations.

In the agentic coding world our job is to provide leadership to our agents, reduce friction, and appreciate what is happening as it happens. After that we should do the best thing we can do: get out of the way.

Check out John Boyd’s original slides from 1987: https://www.coljohnboyd.com/#pdf-organic-design-command-control-pdf